What is DevOps and Why Use It? (90 Days of DevOps)

What exactly is DevOps?

DevOps is an approach to culture, automation, and platform design intended to deliver increased business value and responsiveness through rapid, high-quality service delivery. This is all made possible through fast-paced, iterative IT service delivery.

Source: redhat.com

DevOps arose in response to common pitfalls that have historically plagued organizations trying to build and deliver software. A couple of examples include lack of communication within the organization producing the software, and a long development cycle prone to delays.

If you are lucky enough not to have lived through the types of problems that DevOps aims to address, then the well-known book The Phoenix Project will allow you to experience these challenges vicariously by reading all about a fictional company’s struggles.

Major priorities of the DevOps approach include efficiency, teamwork across roles, and automation, all as a means to build quality software and get it to end users faster and more reliably.

Responsibilities of a DevOps engineer

Some purists will argue that there is no such thing as a “DevOps Engineer”, since DevOps itself is a culture, rather than a job role. Either way, some things are understood about engineers when “DevOps” is part of their job title:

They are at least somewhat conversant in both the software development process and in IT operations. Blurring the lines between development and operations is a core theme of DevOps, since communication and collaboration between these (historically separate) roles has been shown to improve software development outcomes.

They have a very broad-reaching computing skill set. There is just an amazing amount of complexity involved in building resilient, secure software and serving it to end users at scale. Having a broad foundational understanding of the many moving parts is required in order to help optimize the process.

Here is an often-cited (and arguably daunting) diagram of topics for a DevOps engineer to learn: https://roadmap.sh/devops

Note that it’s not about becoming an expert in every area, but rather a broad foundational understanding and knowing how the parts fit together. Also note that it ends with “Keep Learning,” since the processes and technologies involved in building and serving software are constantly evolving.

The DevOps lifecycle

A DevOps lifecycle is a type of software development lifecycle (SDLC) that has been tailored to reinforce DevOps practices. Two key features of a DevOps-style SDLC are repetition and automation. Repetition is important because the idea is to deliver quality features and fixes often, and automation is a crucial tool for ensuring efficient repeatability.

Types of automation typical of a DevOps lifecycle include:

-

Continuous Testing, for identifying problems early in the development cycle

-

Continuous Integration, for building the software often and helping quickly identify any build-breaking changes

-

Continuous Deployment, for sending new working builds to a suitable runtime environment where they can be consumed

-

Continuous Monitoring, for detecting runtime issues in production, and notifying the appropriate people

DevOps & Agile

The Agile and DevOps approaches are complementary and frequently taken together, since their goals overlap and help reinforce each other.

Agile focuses on rapid iteration and frequent communication between an organization and its software consumers. These focuses aim to make the software development process more “agile,” as in the development direction can respond to frequently-changing demands.

DevOps, with its focuses on automation and organizational communication, help achieve the smooth rapid iteration demanded by Agile.

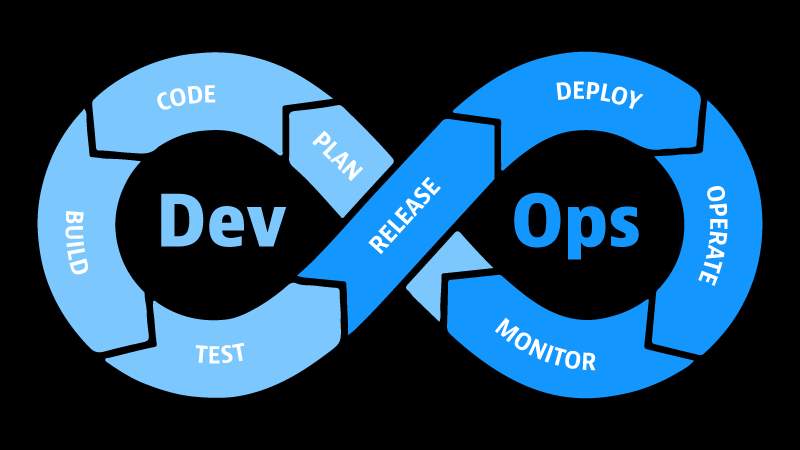

Plan > Code > Build > Testing > Release > Deploy > Operate > Monitor >

When a DevOps lifecycle is diagrammed, it is often depicted in the shape of an infinity symbol or as a circle, highlighting a focus on iteration of the entire process.

For example, below is the diagram presented in the 90 Days of DevOps project:

Note that an organization can easily choose to divide its own process into more or fewer steps as suits its needs.

Below is a breakdown of the steps depicted above:

- Plan: Agree on requirements/goals for the current iteration through the cycle

- Code: Write software source code to meet those requirements/goals. Frequent code commits are encouraged at this stage, which in turn trigger automated processes that assist with the next steps in the cycle.

- Build: Convert the code to a format that is usable in production, e.g. compile it or create a Docker image. Automation is possible via Continuous Integration.

- Test: Test code for quality / vs. requirements. Automation is possible via Continuous Testing/Integration.

- Release: Formalize the current iteration of the software as a new release. Examples of activities in this step: pushing a Docker container image to a registry, tagging/publishing a new release in GitHub. Automation is possible via Continuous Delivery.

- Deploy: Send the new software release to a compute environment where it becomes available to end users. Automation is possible via Continuous Delivery/Deployment.

- Operate: The software is now running in a production environment and available to its end users, who use the software and come back to the software organization with feedback.

- Monitor: Software/compute environment logs and metrics are recorded/analyzed to determine how well the software is working in production. Automation is possible via tools such as Prometheus.

- Back to Plan: Information gathered from the current iteration of the cycle (e.g. customer feedback, software performance in production, monitored metrics, bugs) is used to decide requirements and goals for the next cycle.

DevOps - The real stories

Amazon

-

Over the course of eight years in the aughts, Amazon gradually refactored their monolithic software into microservices, each handled by a small team. This allowed for improved team communication, faster iteration and better responsiveness to customer demands. A decoupled microservice architecture made it easier to change individual features without disruption to the overall product.

-

The new process significantly improved Amazon’s software release speed, but it left them with a backlog of features/fixes waiting to be manually deployed to a production environment. Their solution was to create a pipeline using internally-created tooling, which automated the process of building, testing, and deploying their software.

Over the years, Amazon’s time to deploy new releases has gone from months (under their legacy monolithic architecture), to weeks (after implementing microservices), to under an hour with the help of a pipeline. This has been further optimized over time; as of 2018, their internal developer surveys indicated multiple deployments per second.

Netflix

-

Netflix implements an unique brand of DevOps culture rooted in complete trust in their developers, to the point where every engineer has write access to production. This works for them for a couple of reasons:

-

Although uptime is important, the Netflix video entertainment platform is not a mission-critical application. In Netflix’s field, innovation is prized above reliability.

-

Such freedom is balanced with responsibility. Netflix can maintain a culture of full trust because they reinforce it by hiring for an exacting culture fit.

-

-

Other features of Netflix’ DevOps lifecycle include many small teams, hundreds of microservices, thousands of daily production deployments, and tooling created in-house and made publicly available as open source.

NASA JPL

-

In contrast to Netflix, JPL’s software demands mission-critical reliability, since that software can determine the success of long-term robotic space missions. These missions take about 9 years from concept to launch. As such, JPL’s software must meet a long list of formal requirements.

-

At JPL and other government agencies, legacy software and infrastructure is commonly encountered. JPL modernized their legacy systems using containers, which sped up innovation by making it much easier to prototype and thoroughly test new ideas.

Real stories sources:

<< Back to 90 Days of DevOps posts

<<< Back to all posts